Field Notes from Antiquity | 002

Canon of Wonder: Geometry, Emotion, and the Human Body in Classical India

What could a fashion sketch and a temple murti possibly have in common?

Quite a lot, as it turns out.

In most fashion schools today, students are taught to draw the human body using a proportion system known as the nine-head rule: the figure is divided vertically into nine equal units, each the height of the head. This system is often attributed to Vitruvius, the 1st-century Roman architect, and popularised by Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic Vitruvian Man in the 15th century.

But centuries before Vitruvius, ancient Indian sculptors had developed an elaborate system of iconometry that treated the human body as a vessel of proportion, spirit, and emotion. This system was not created to flatter the human form, but to express something larger: to make space for divinity to inhabit matter.

And yet, these systems are almost never credited. The canon that governed gods, temples and bronzes across millennia was quietly removed from the global conversation.

This is a note of return. This is the world of Tālamāna Paddhati: the canon of sacred measurement in Indian art.

The Tālamāna System: Sacred Mathematics of Form

In classical India, the body was never just a biological vessel. It was a sacred geometry, a form meant to hold rasa, bhāva and shakti. To sculpt a body was to sculpt a cosmos.

The system that governed this act was called Tālamāna Paddhati.

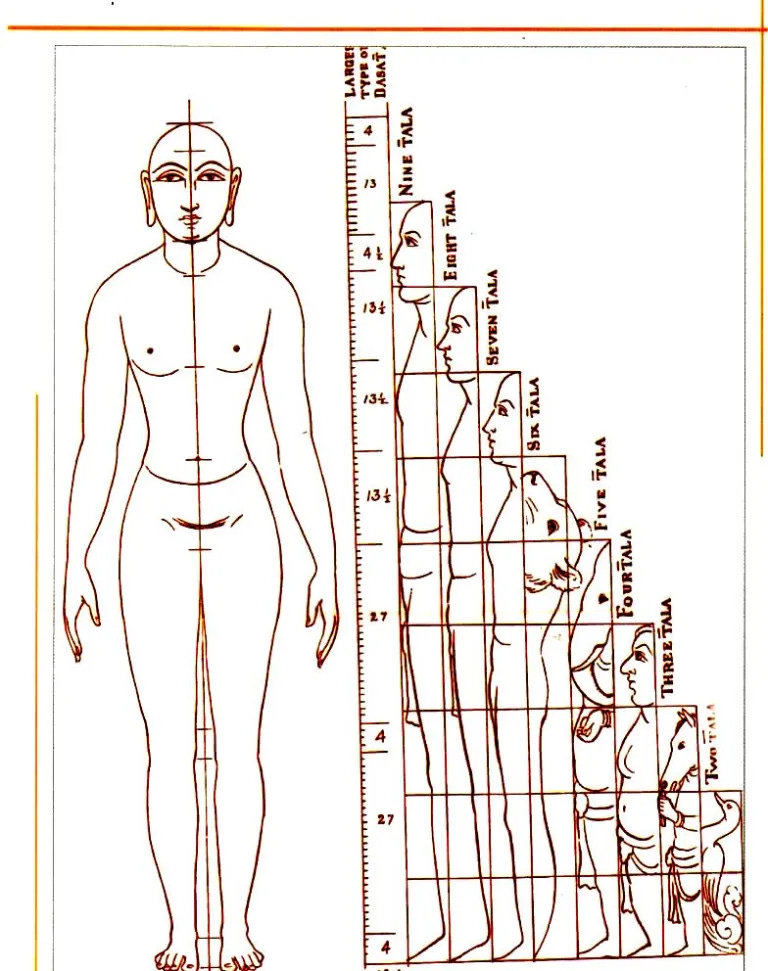

Taala referred to the hand span from the tip of the middle finger to the wrist. Māna meant measure. Together, they formed a system where every divine or human form was constructed using talas as base units. Each tala was further divided into aṅgula (finger breadths). The system scaled from grain to fingertip to body, each unit building upon the one before.

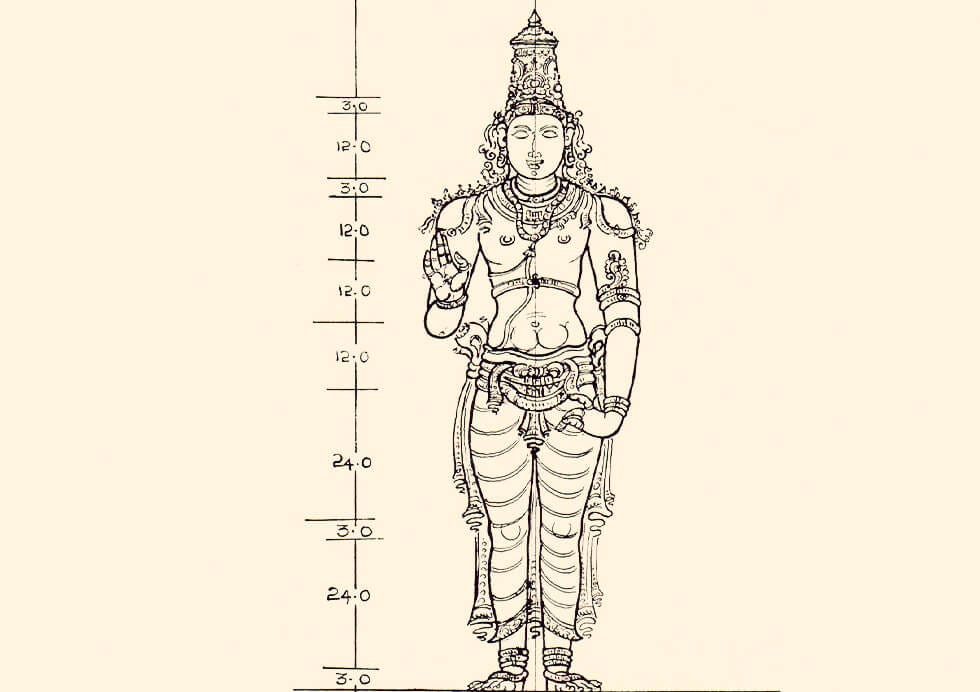

Each tāla is divided into 12 aṅgulas (finger-widths), and the height of a standard murti, known as Daśatāla was 10 tālas, or 120 aṅgulas. Four extra aṅgulas were allowed for corrections, extensions at joints, or symbolic additions.

There were two common methods of applying this grid:

The Fixed Unit Method: using the sculptor’s own body, palm, or finger, as the measure

The Divided Block Method: mapping out a mathematically scaled grid, using objects like grains or small stones as anchors

For example, a 9-tāla sculpture would place the navel at 4.5, the chest at 3.5, and the feet at 9. The face, mapped on a 3-aṅgula grid, would assign 1 aṅgula each to the nose, mouth, and eye spacing. This allowed sculptures to be replicated at any scale, from miniature bronzes to towering temple icons, without compromising proportion.

From Dust to Divinity: The Microscopic Measure

Some canonical texts begin not with the body, but with the atom.

The Brahmīya Citra Karma Śāstram, a rare Vaishnava Āgama text from the 5th–6th century CE, and the Bṛhat Saṃhitā by Varāhamihira (6th century CE) describe the starting point of measurement as the tiniest visible unit, a particle seen when sunlight filters through a lattice.

That particle is the paramāṇu, the atomic spark at the origin of scale.

The hierarchy of measurement unfolds from there:

8 paramāṇus = 1 aṇu

8 aṇu’s = 1 reṇu (speck of dust)

8 reṇus = 1 romāgra (tip of a single hair)

8 romāgras = 1 likhya

8 likhyas = 1 yūka (tiny insect)

8 yūkas = 1 yūva (barley grain)

8 yūvas = 1 manāṅgula

In practice, one aṅgula was the most useful unit as a a finger, because some of these were only visible to the sages. Every element, from a finger joint to the height of a tower, was calculated in multiples of these.

The Grid of the Human Form: Uttama, Madhyama, Adhama

Indian sculptural manuals didn’t depict the human body as a neutral subject. Each figure type had its own grid, based on its spiritual status:

Uttama (divine or godly): 120 aṅgulas

Madhyama (noble or heroic): 108 aṅgulas

Adhama (mortal or human): 96 aṅgulas

The most refined and often used was the Uttama Daśatāla, and the Brahmīya Citra Karma Śāstram gives detailed prescriptions:

In a standard 124-aṅgula statue:

Face: 13.5 aṅgulas

Neck: 4

Torso: 13.5

Thighs: 27

Arms: 22.5

Hands: 13.5

Nothing was left to guesswork. The angle of a toe, the arch of a brow, the rhythm of a shoulder, each was drawn from canon. Rasa was built into structure.

This system enabled exact replication and transmission across generations, from one sculptor to the next, from temple to temple.

Bhāva in the Body: The Sculpture that Breathes

Proportion alone does not move us. What makes a murti stir emotion is bhāva: posture and expression.

Classical sculptors codified five canonical postures:

Samabhanga — the fully balanced pose

Abhanga — a gentle hip bend

Dvibhanga — two bends (neck and knee)

Tribhanga — three graceful curves (neck, torso, hip)

Atibhanga — an exaggerated form, rarely used

These were not arbitrary stylisations. Each curve was precisely measured. The tribhanga, one of the most iconic postures in Indian sculpture, involved specific angles: a 15° neck tilt, exact hip drop, and contrapposto stance engineered to radiate rasa, the aesthetic essence of emotion.

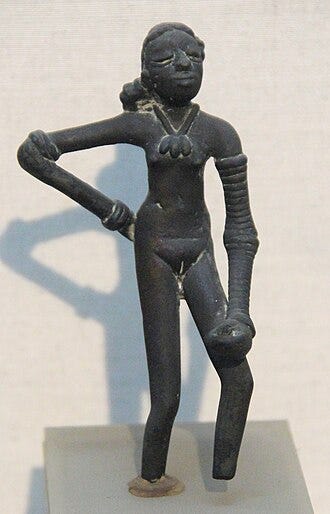

The earliest known example of Tribhanga appears in the Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro, dated around 2500 BCE.

Over 2,000 years later, the 12th century Mohini from the Chaulukya dynasty shows a more extreme version, the form now fully infused with sensual grace and spiritual magnetism.

The result was not just a depiction of a god or dancer. It was a form that breathed.

Rasa: Design for Feeling

The Nāṭyaśāstra, composed between 200 BCE and 200 CE, offered the foundational theory of rasa—the aesthetic flavour a work evokes. It described nine rasas, each with matching bhāvas (emotions), anubhāvas (responses), and sāttvikas (involuntary reactions).

The nine rasas were:

Śṛṅgāra – Love, attraction

Hāsya – Laughter, joy

Karuṇa – Pathos, compassion

Raudra – Anger, fury

Vīra – Courage, heroism

Bhayānaka – Fear, anxiety

Bībhatsa – Disgust

Adbhuta – Wonder

Śānta – Peace, stillness

Sculpture was never just about likeness. It was about evocation. A still figure could suggest motion, a smile could imply eternity.

Examples:

Durga slaying Mahishasura, Mahabalipuram – Raudra Rasa

A couple at Harshmata Temple – Śṛṅgāra

The Grid in the Temple

What applied to the body applied to space. The same tālamāna system governed temples.

Each temple was a cosmic body:

Sanctum (garbhagṛha) = womb

Mandapa = chest

Tower (śikhara) = head

Entryway = feet

The Kailāsa Temple at Ellora (8th century CE), carved from a single monolithic rock, demonstrates this idea in full glory. Its proportions are not decorative, they are structured, rhythmic, governed by invisible grids. Every pillar, deity niche, and stair corresponds to an underlying bodily measure.

Sitting and marvelling at the Kailasa temple, a more detailed post on this later.

Precision in Detail: Br̥hat Saṃhitā’s Metrics

Varāhamihira’s Br̥hat Saṃhitā contains one of the earliest and most elaborate accounts of sculptural proportion.

Selected details include:

Face = 12 inches

Nose, forehead, ear, chin = 4 inches each

Eye = 2 inches wide, pupil = two-thirds inch

Mouth = 2 inches long, 1.5 inches open when speaking

Distance between nipples = 10 inches

Navel = 12 inches below heart

Pedestal = one-third of seven-eighths of door height

Thighs and shanks = 24 inches each

Arms = 12 inches; forearms = 6 inches

Palm = 6 by 7 inches

Middle finger = 5 inches

Shoulder width = 18 inches

Entire body height = twice the height of pedestal

Every detail, from nails to nostrils, had a measure. These weren’t estimates, they were prescriptions. More on this text in the subsequent posts.

The Sculptor as Architect of Energy

The word for sculpture, pratimā, does not mean statue. It means “reflection” or “embodiment”. The murti was not just a likeness, it was a vessel, activated through ritual once the proportions had made it worthy.

A deity would not enter a form unless it resonated. The act of making was the act of inviting. Geometry was not just aesthetic, it was spiritual.

The sculptor, then, was not just a technician. He was a priest, a geometer, and a transmitter of rasa.

A Canon of Wonder

When you stand before a Chola bronze, you do not just see a sculpture. You feel rhythm in metal. When you observe the sinuous figure of a Gupta-era Yakshi, you do not just admire form, you recognise poise, measure, and emotion distilled.

This is the genius of the Indian canon:

It never separated aesthetics from spirit, or science from feeling. It made the body a map of the cosmos, atom to ankle, pupil to pedestal.

Today, when the world credits the nine-head croquis to Renaissance men, we might ask what was lost in translation.

Or what was quietly forgotten.

The Geometry of Feeling

Across cultures, the body was measured with intent. These systems were not just anatomical, but emotional. In ancient Egypt, a grid used eighteen units from heel to hairline. In Greece, Polykleitos wrote of perfect ratios. Vitruvius, later drawn by da Vinci, placed man inside a square and a circle. In China, the Tang canon measured nine heads. In Yoruba art, the head was oversized to symbolise spiritual power.

India went further.

Texts like Śilpaśāstra, Bṛhat Saṃhitā, and Brahmiya Chitra Karma Śāstra did not only define proportion. They calibrated bhāva and rasa — inner state and felt emotion. A murti could be four or ten heads high depending on what it had to express. Every finger, joint, nail and bend was measured. The tāla system used the human body as ruler. Micro-units extended from the sunbeam-sized paramāṇu to the barley-grain yava to the finger-width aṅgula. From temple sculptures to home idols, form was never without feeling.

What is most astonishing about this system is not its detail, but its intent. These measurements were never about control. They were about transcendence. About building presence into stone. Emotion into geometry. A lifted brow, a curve at the hip, a palm raised in blessing: each drawn not from guesswork, but from an ancient system of feeling. Bhāva, not just balance. Rasa, not just rule.

And yet, most of the world learns only da Vinci. We forget that India has its own living geometry, rooted in craft, rasa, and a different idea of beauty. A canon where proportion was only a beginning. And feeling was the final measure.

Sources

Tala System and units of measurement

https://sreenivasaraos.com/2012/09/09/temple-architecture-devalaya-vastu-part-eight-8-of-7/

Shilpa Shastras - Wikipedia

https://www.scribd.com/document/489199655/Temple-Architecture-by-Sreeneevasan

Vitruvius, Nine Head:

https://jsklensky.webspace.wheatoncollege.edu/Art_Spring17/inclass/proportion/Vitruvius.html'

https://www.amikosimonetti.com/life/drawing-the-fashion-figure-with-9-heads-proportion-part-1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_canons_of_body_proportions?utm_source